The Point Of Engagement: Part II

For Swing the Fly Magazine

November, 2022

“After hours, days of casting and casting and casting on the Grande Ronde…” Wolters told me, resurrecting the memory, “…one day, one cast, everything just stopped.”

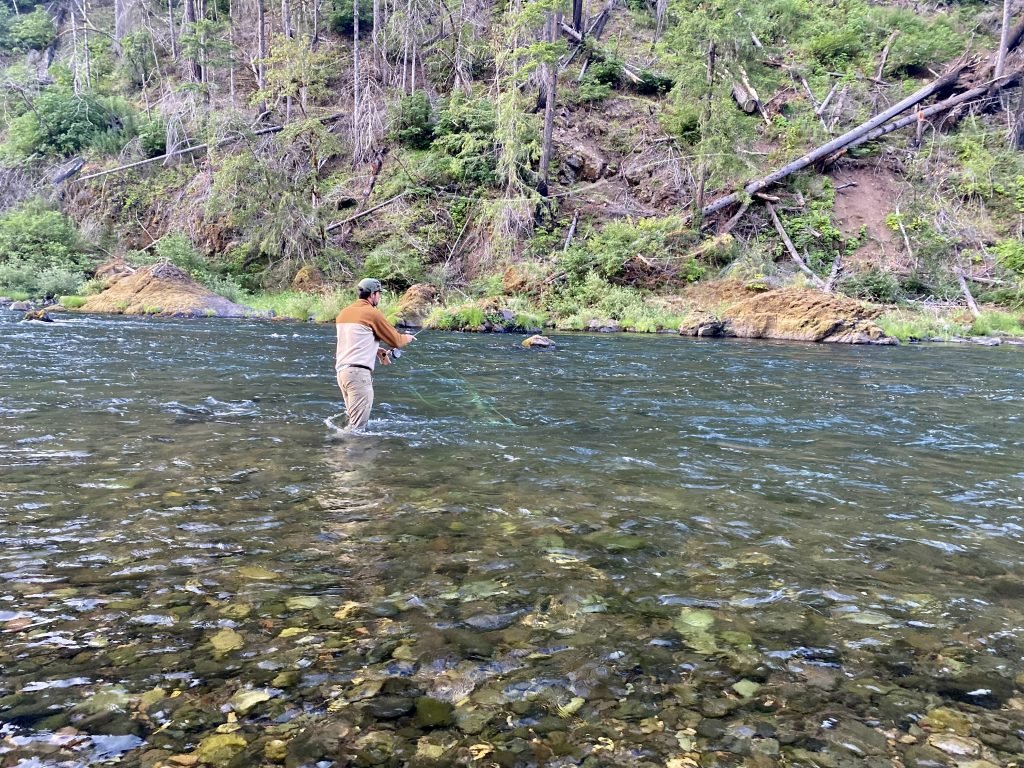

Wolter is of the most romanticized form of steelheader: big rods, long effortless casts, slowly swinging classic patterns on long floating lines down gravel bars.

“You want the same amount of fly line out, the same lift on every cast, the sweep, the same mend,” Wolters preached. “Consistent. Consistent. Consistent. A 100-foot cast or a 40-yard cast. Doesn’t matter. Make it the same, and cover every inch of that water between you and the fly. Step, and do it all again.”

Together, we watched the seasons change and my casting progress on the Boise.

It won’t be long until we share a run; he’ll go first.

Arriving at the North Umpqua river in the last minutes of light, I realized something odd about nearly all the anglers I saw as I barreled down the watershed racing to my campground for the week.

They all were perched atop rocks pretty damn far out in the river.

Where were the long, clearly defined runs? Where were the seams I’d trained my eye to find? It was overwhelming, realizing the dozens of hours spent casturbating had done little but make me a spectacular practice player. I was an athlete built to play in a dome.

The next morning, before dawn, I quickly met up with Rob Burkius, a southwest Oregon local and owner of Swing the Fly sponsor Two Handed Hardware. He laughed when I asked him about the anglers standing on those “perches”, telling me they were called casting stations and it was a bit of a trademark characteristic of the North Umpqua.

“From stations, you’ll start short, then range out, then extend your cast. Work the spot, then walk down to your next station.” Berkius explained after my initial casts sailed well past their intended targets. “But watch your step. The basalt will get ya.”

After countless swims, snags and the like, I began to see the bubble lines, seams and submerged rocks. The mends began to happen naturally without thinking.

All from these dastardly stations, more in the river than beside them, and made of the single slickest geological material on the planet.

Over cold beers and a hot afternoon sun, I talked with Kirk Blaine, leader of the Steamboaters, a local organization that works to protect the famed North Umpqua. He shared how the North suffers from nearly all of the same threats steelhead do across the Pacific Northwest.

After hearing so much of the closure of the river to fishing after the catastrophic steelhead returns of 2021, I had earnestly tried to read everything I could, talk to anyone I could find. I wanted to avoid being an experience whore, parachuting in, reaping my benefits and hightailing it out.

I was ready to talk shop about unnecessary hatcheries. I was ready to hear about ancient dams, impeding federally listed salmon and steelhead, preserved for the sake of ideal water skiing. I was not prepared to see evidence of a wildfire, which obviously had recently engulfed the river valley.

“The fire blew up overnight, and those of us over in town had to wait and see what was going to happen. It was agonizing,” Blaine said, speaking to the 2020 Archie Fire which burned more than 130,000 acres along the North Umpqua, leaving much of the river banks exposed to direct sunlight, aiding in increasing water temperatures.

Some things get through the cracks when you’re 500 miles away.

Blaine, Berkius and others, shared personal stories of resilience since the fires and in the myriad of other issues facing not only North Umpqua, but across southwest Oregon. Most spoke of the legacy of the recently passed Frank Moore, whose stewardship and leadership for the community will live on in perpetuity.

“If people can take away anything from visiting and fishing, I’d hope it would be the history and passion for conservation for this river and its fish,” Blaine said. “It’s something special.”

Weeks later, Rich Simms, one of the founding members of the Wild Steelhead Coalition, made a statement which provoked me to more fully process my time on the North Umpqua.

“I think everyone should understand, should consciously take personal responsibility for their impacts, because even small individual impacts are compounded,” he said. “There’s no room for just taking anymore. The true takeaway is introspection.”

At the root of it all, for me, maybe for others, is the pursuit of a moment of insight into the countless connected ecosystems, the challenges – natural and man-made – that are intertwined in a steelhead’s life history.

All of it, tangled in one single, living, cartwheeling-across-a-river moment.

On my last night on the North Umpqua, as the sun set behind the northern wall of the valley, a bulge formed under my homemade muddler pattern skating across the water’s surface. Managing my instinct to set the hook, the reel began to sing and my breath stopped. Ten, twenty, thirty yards, the line flew from the reel; the fish, whatever it was, ripped back towards river right, where I stood atop my perch. As it neared the bank, it slowed, and I lost tension on the line.

I gently, ever so gently, tugged the rod towards the bank, and felt only a slight bump as the fly was ripped from the fish’s mouth and fell to the rocks below.

Just like that, it was gone.

A long time ago, someone told me every piece of river should be treated like it’s someone’s favorite place in the entire world, because it probably is.

For anadromous species, the journeys they take and the challenges they face can be truly colossal in scale. Understanding even a single watershed is a colossal effort, especially from a distance. While it’s admirable to try to understand the often international scale issues facing seafaring species, I suspect the engagements we seek can be had – can be enriched – by seeking out, getting to know, trusting and supporting local stewards.

Folks that not only use or know, but love and tend to individual rocks, that know the names of the seams, pools or riffles, that have institutional knowledge of a Place, make progress – both in conservation and your fishing – a bit more relatable and a lot more attainable.

The rock I had precariously stood on was someone’s favorite station in the entire world.

Sure, sometimes it’s big casts, long lines and long picture perfect runs, but, the spots where everything stops, they’re found intentionally, and consciously, inch by inch.

Casting a spey rod, you end there. Conserving a species, you start there.